Harlem Hellfighters After the War

Horace Pippin's experiences during the war are important for understanding his life after. The soldiers of the 369th, endured gassing, shelling, firefights, and loss of life only for those who survived, like Pippin, to face racism, segregation, discrimination, and lynching by white Americans. Healthcare for Black veterans did not exist. There were no VA benefits, GI Bill, or any other mechanisms to support veterans, regardless of injury or amount of trauma.

But Black veterans endured.

After adapting to his war injury, Pippin continued to make art. In the late 1930s his work caught the attention of an art dealer, who then brought Pippin's paintings onto the national stage. Pippin's work reflected his experiences at war, Black life, and American racism.

They are beautiful, joyful, and often painful. View some of his work held by the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

Warfare and the threat of returning to the battlefield still loomed over many veterans of WWI. During WWII, American men were required to register for the draft. Pippin, despite sustaining combat injuries during WWI, receiving no support from the military, and being in his 50s, had to fill out "Fourth Registration" draft cards.

These cards are part of what is called the "Old Man's Draft." On the front his vocation is listed as an artist. On the back we can see that his hair color is selected as "gray" and that he had leg, thigh, and shoulder wounds.

Art After the War

Mr. Prejudice

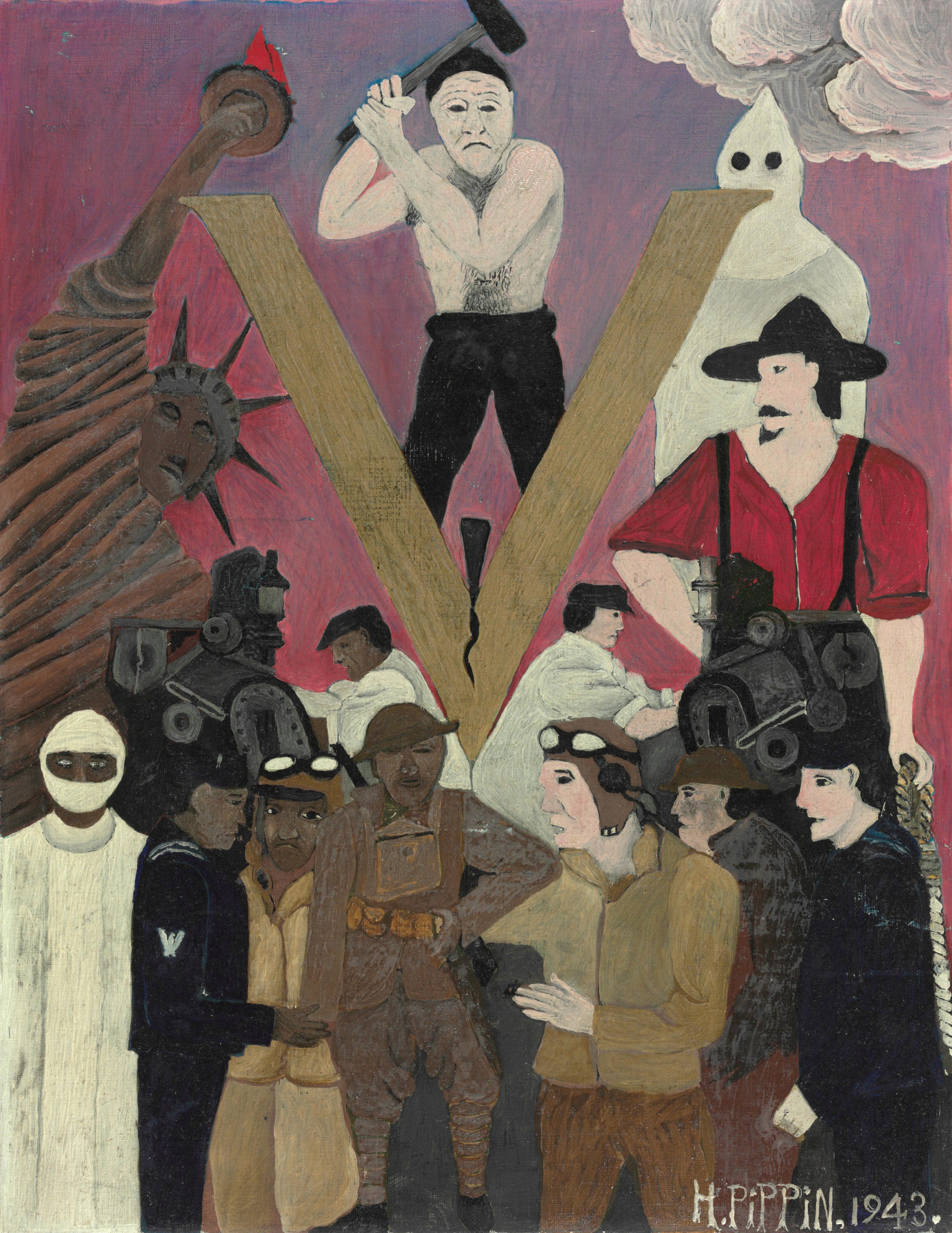

Horace Pippin created many works of art. Mr. Prejudice (1943), featured here, is an unflinching look at how the ugly face of racism and prejudice threatens the Double Victory campaign. The Pittsburgh Courier popularized the campaign in 1942, where the Double Victory stood for defeating fascism and fighting for freedom abroad and domestically.

Below is the description for Mr. Prejudice as written by the Philadelphia Museum of Art.

"Human rights and social issues often figure in Pippin’s work, but this painting is particularly overt in its treatment of racism. Clouds hover over a hooded member of the Ku Klux Klan and a burly white man holding a noose. The two menacing figures stand opposite the Statue of Liberty, here painted brown instead of green.

At the center, Mr. Prejudice drives a wedge into a symbolic V for victory, segregating white and black machinists and servicemen. Pippin includes himself as one of the soldiers, wearing a World War I uniform, with his wounded right arm hanging at his side."

Horace Pippin's life after the war, as well as the lives and work of many other Black men and women, illustrate just how long and deep the roots of the fight for Double Victory are. Just as the civil rights movement did not start with the 1955 Montgomery Bus Boycott nor end with the passing of the Equal Rights Art in 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965, the fight for freedom domestically is much longer than WWII.

Noble Sissle, the Harlem Hellfighters Band, and the Harlem Renaissance

Many Harlem Hellfighters went on to express themselves artistically and achieve great things after the war. Noble Sissle (1889-1975) and James Hubert "Eubie" Blake (1887-1983), veterans of the Harlem Hellfighters Regimental Band, continued their musical careers after the war. Sissle and Blake earned tremendous respect as musicians, playing pivotal roles in the Harlem Renaissance and jazz scene.

Pippin, Sissle, and Blake are American heros, accomplished artists, and examples of endurance.

But many Black veterans and veterans-of-color, regardless of what war or wars they served in, are unknown to history.

They served, they survived, and were left to navigate life after the war often with no support from the VA or benefits from the government.

The medium of digital history reviewed over this exhibit holds possibility for uplifting these quieter, but no less important, stories. By creatively displaying surviving records, drawing on existing oral histories, reaching out to living veterans to record their experiences, and putting them into conversation with each other in a digital space, we can learn more about the lives of veterans after the war.